Our record-breaking $1.2 billion in new research awards this past fiscal year was a wonderful accomplishment and justifiably newsworthy. But have you ever considered the enormous amount of grant applications that need to be submitted to reach that total? Submitting a grant application in no way guarantees an award, and the probability of not being funded is always high.

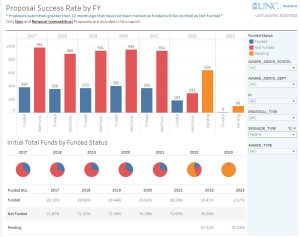

In reviewing data for FY21, Carolina researchers submitted close to 1,300 new and competitive renewals for federal grants (FY22 and FY23 still have many ‘pending’ proposals since they were so recently submitted). Federal grants offer a better picture of the process because non-federal grant applications are often solicited by a funder and/or invite applications that have a much higher chance at being awarded. In FY21, just over 28% of UNC’s new and competitive renewal applications for federal grants received a Notice of Award, meaning the vast majority were not funded. Those of us who were not funded in FY21 were in good company — yes, including me, and I’m working with collaborators on a new submission as you read this!

Even our most seasoned investigators and senior faculty get applications turned away. In recognition of the 72% of submissions that did not receive awards, I wanted to share reflections from some of our most well-known investigators.

Provost Chris Clemens shared some words from his own experience with me:

“When I came here, I was hired to build a facility instrument for the SOAR telescope. We had raised about half of the necessary funds from a private source. But we needed an NSF grant to complete it and to build credibility within the community. My first submission went down in flames, with some very harsh words from one reviewer. In response, we added capacity to the team, visited other successful teams to solicit advice, and revised the grant substantially. The next round was a year later, and we were successfully funded. Even now, with much more experience, I can still get frustrated that it takes three cycles to get our work funded. Competition is fierce, but persistence always pays off.”

The School of Medicine’s Vice Dean for Research Blossom Damania also shared these sentiments:

“As a junior investigator, my batting average for grant awards was one out of nine, i.e., only one out of every nine grants I submitted got funded. And I submitted a lot of them! Now as a senior investigator, my average is slightly better — one out of four. As a senior researcher, I understand that grant rejections are par for the course. Persistence really does pay off. You will eventually get that grant if you keep trying.”

I asked Professor of Epidemiology and grant writer extraordinaire Kari North what words of wisdom she’d impart to junior faculty facing rejection and she said:

“Each rejection teaches me to be creative and think of new ways to get my work funded. If you have a good idea and it fills a major research gap, keep re-crafting your proposal and try again.”

William R. Kenan, Jr. Distinguished Professor, and world renown coronavirus expert, Ralph Baric added:

“I personally have had dozens of unscored NIH grants during my career and have been ridiculed by reviewers more than once as being an ignorant half-wit, but this has been layered across a backdrop of success. Don’t be hesitant to take some chances (leaps of faith/belief) during your career, as it’s not only about writing successful grant applications, but also, and sometimes more importantly, about building collaborations and interactions, exploring new spaces, and thinking completely out of the box about new research possibilities that might become lucrative in the future.”

I can also share a bit from my own experience. I am no stranger to the dreaded “not discussed” grant. Over time, I have learned not to take rejections to heart. I also seek to understand what exactly the reviewers didn’t like and learn how to resolve those issues. Damania also noted, as a reviewer, “it is important to remember to keep in mind that there is a person on the other end reading my comments and that they are human, so I need to be rigorous and fair, but also kind and reasonable in my critiques.”

I find that talking through reviews with my collaborators can make a world of difference and — in most cases — the revised grant application is vastly improved after we make necessary adjustments. Plus, it’s always nice to commiserate (and sometimes share a salty word or two about the reviews) with collaborators. The most exciting part of the process is when a reviewer comment leads you to an opportunity to engage a new collaborator from a different discipline which then invigorates the research. This can open new avenues and new projects.

After dedicating hours and hours to crafting your grant, it is hard not to take reviewers’ critiques personally. I find it easiest to put the summary statement aside for a few days before coming back to reading it carefully. It is important to remember that review panels are comprised of experts from a variety of disciplines and perspectives who offer feedback that may be unexpected.

Rather than dismissing that feedback, try to take time to understand what exactly the reviewer is suggesting and why. I often find that sharing the reviewers’ comments with my peers or senior colleagues can help sort through the types of responses that are needed – and help identify any blind spots.

If stories such as these have inspired or encouraged you, I invite you to follow our Research UNCovered series. In these bi-weekly profiles, Carolina researchers share firsthand accounts of encountering and overcoming setbacks in their careers, and personal stories of how they ultimately overcame those challenges.