Restless Skies

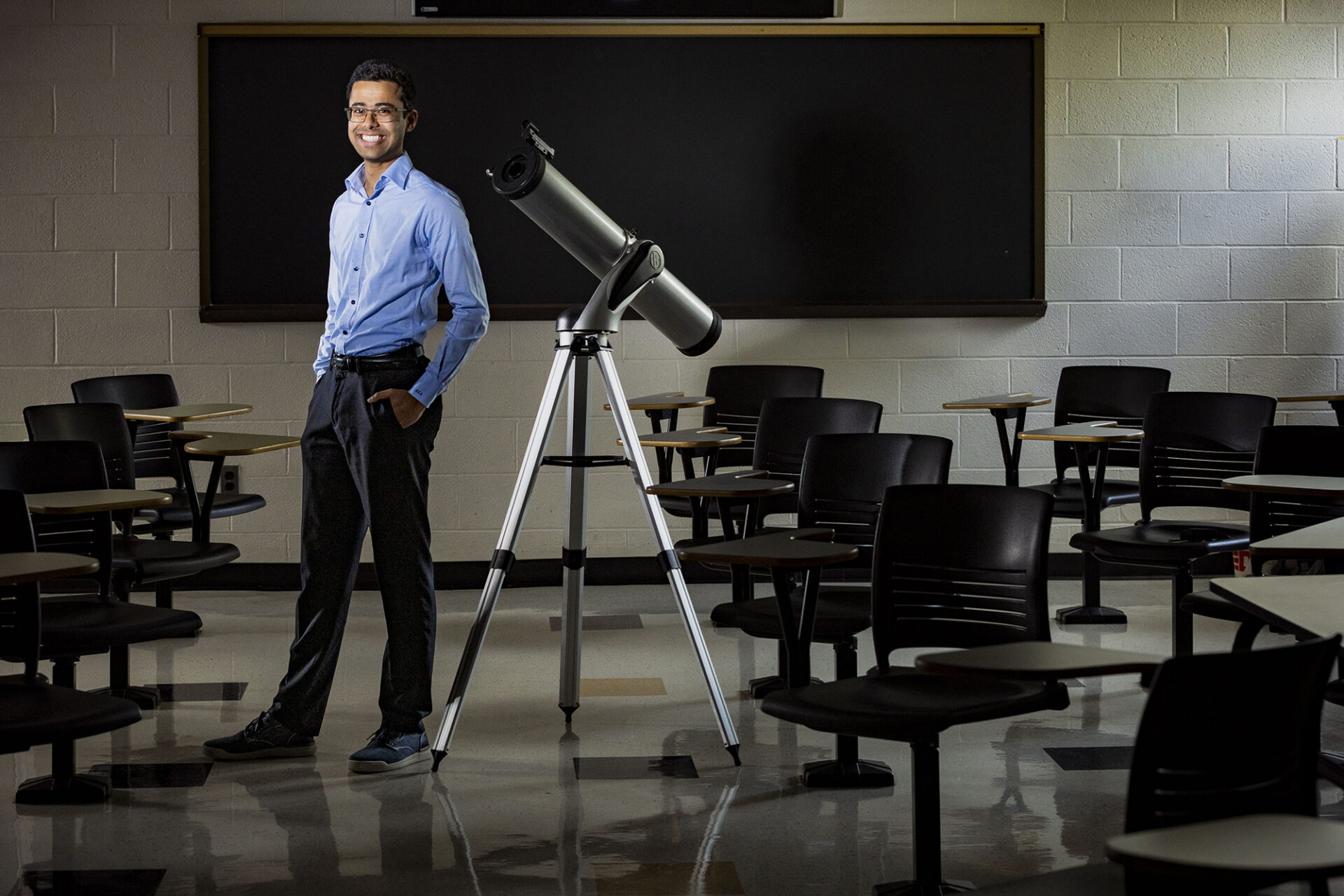

Anish Aradhey explores how stars and galaxies evolve — and what they can teach us about the universe.

September 16, 2025

Impact Report

20,000+ undergraduate students will participate in research across disciplines — from the humanities to health care — during their time at Carolina.

Support from initiatives like the Robertson Scholars Leadership Program encourages the next generation of leaders to use their education to positively impact the state, nation, and world.

As Anish Aradhey sets foot into the Southern Astrophysical Research Telescope in Cerro Pachón, Chile, his jaw drops while gazing up at the cavernous ceiling. The room’s focal point is a massive 4.1-meter mirror that collects light from the night sky, reflecting an image for the astronomers to analyze. In an adjacent room, a visiting astronomer stands at the control console, glancing between monitors displaying live feeds from the telescope’s cameras.

For Aradhey, this moment was years in the making.

During the summer of 2025, the UNC-Chapel Hill junior landed a coveted position with the International Gemini Observatory, diving headfirst into research on some of the most mysterious structures in the universe: merging galaxy clusters. His project focused on how these cosmic collisions shape the evolution of galaxies and what they can reveal about dark matter — a substance that makes up most of the universe’s mass but remains invisible to our eyes.

But his journey to this mountaintop telescope didn’t start with dark matter or data tables. It simply began with curiosity.

A universe of questions

Since middle school, Aradhey has kept John F. Kennedy’s famous “moon speech” saved on his laptop’s bookmarks bar. A reminder that pushing boundaries, embracing wonder, and chasing hard questions is what makes science meaningful.

That mindset is what led him, as a high school student in Harrisonburg, Virginia, to cold-email dozens of science professors at James Madison University, hoping somebody would let him into their lab. Eventually, one astrophysicist said “yes.” She began sending Aradhey pre-recorded introductory lectures for her astronomy classes and invited him into her lab, teaching him how to retrieve and analyze the data she used.

Eventually, Aradhey began working on a project of his own — one he started at 17 years old and has continued as a student at Carolina. Interested in the big questions, he wanted to investigate how galaxies evolve, specifically in the enigmatic active galactic nucleus (AGN) phase. This occurs during a galaxy’s evolution when its central supermassive black hole is actively consuming surrounding matter. It’s what he calls their “rebellious teenage phase.”

“We think that almost every galaxy has a central supermassive black hole, including our own,” Aradhey explains. “And during some point in their lives, matter falls onto the black hole and forms a superheated, glowing disk that can be detected with telescopes.”

But scientists still debate what causes this dramatic phase. Does it happen because galaxies interact? Or can it happen in isolation?

For the last four years, Aradhey has analyzed the loneliest galaxies in the universe, called cosmic voids — systems so far away from their neighbors that they barely have a chance to interact.

When galaxies enter the AGN phase, they emit a powerful glow across the electromagnetic spectrum. Aradhey analyzes infrared light readings, the kind of heat-based light we can’t see with our eyes. He looks for certain signatures in the infrared light to identify when the black hole at the center of a galaxy is acting up.

“If we see a lot of variation in the galaxy’s light, that tells us that a galaxy is probably snacking on matter around it and ripping apart that matter, entering the AGN phase,” he says.

Using data from NASA’s NEOWISE telescope, he examines how the brightness of 300,000 galaxies changed over time, searching for patterns in the light curves: galaxies that shimmered, dipped, or flared.

What he found was striking: Isolation doesn’t stop galaxies from entering their active phase. In fact, some of the most remote galaxies were just as likely, if not more, to host active black holes.

Aradhey suspects it has to do with gas. Galaxies that haven’t had many close encounters with others may hold onto more of the gas they were born with and consume it more slowly. Without disturbances, that gas can unhurriedly spiral into the central black hole, feeding it, sparking the AGN phase, and lighting up the galaxy from the inside out for longer.

The brightest clues

As Aradhey developed expertise in analyzing infrared measurements with his mentor at James Madison University, he began working with Brad Barlow, a professor of physics and astronomy at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Barlow wanted Aradhey to use the same techniques to analyze stars, specifically a strange class of them called hot subluminous stars.

“Hot subluminous stars are almost always binary stars, which means there are two stars that are growing up together, and essentially they mess each other up,” Aradhey clarifies. “One star might start stealing gas and dust from another, gradually stripping away its outer envelope and exposing its core. Or maybe the stars are different in mass, so they evolve at different rates, and one ends up in a completely different phase of life than the other.”

Because they exist in binaries, subluminous stars change in brightness over time. This means Aradhey can use the same NEOWISE telescope data to evaluate how they have evolved.

“The goal of my research right now is to find the most interesting, weird stars out there that are doing things that we don’t expect them to do,” he says.

Aradhey plans to eventually incorporate his observations into his honors thesis, using these stellar anomalies to help astronomers better understand the complex relationships between stars.

When he needs a reminder of what’s possible, he still goes back to that JFK speech bookmarked on his laptop, instilling in him a sense of possibility and inspiration.

“I think there’s a lot of value and pride in being able to do this type of science, even though it’s far away from most people’s daily lives,” Aradhey reflects. “The inspiration that astronomy provides and the zoomed-out perspective that we have when we understand how these big systems work is amazing.”

Anish Aradhey is a junior majoring in astrophysics and marine biology within the UNC College of Arts and Sciences and is a Robertson Scholar at UNC-Chapel Hill and Duke University.