Cynthia Bulik and Patrick Sullivan have created a life full of adventure and research spanning decades, continents, and disciplines.

In 1978, Cynthia “Cindy” Bulik navigated a crowded University of Notre Dame dorm room, looking for a way to ditch a party she was dragged to by her roommate. It was the first-year’s second day on campus, and this was not her kind of scene. But Bulik’s sentiment shifted when she noticed a young man.

“This guy came running into the room totally sweaty, didn’t really interact with anyone, and splashed water on his face,” says Bulik, now the Distinguished Professor of Eating Disorders within the UNC School of Medicine (SOM). “I remember thinking that he was cute. And then I talked to him, and he was smart too.”

Patrick Sullivan, the Yeargan Distinguished Professor of Psychiatry and Genetics within SOM, also remembers that night well. The sophomore was finishing up a run when he returned to a party thrown by his roommates.

“I was totally taken by Cindy from the very start,” Sullivan says. “I remember telling someone I had this feeling that she and I would be together long-term. And I was right.”

Bulik and Sullivan are established researchers who have made groundbreaking progress in the field of eating disorders and genetics both separately and together. They have created a family and community that allows their love for science and each other to thrive.

A transformative semester

It wasn’t long after their serendipitous dorm party encounter that Bulik and Sullivan were an item. For Bulik, it was the first of many fateful encounters Bulik had that semester at Notre Dame. The second happened in a lecture hall, during an intro to psychology course she tried to drop.

“I wanted to be a diplomat and study international relations, not psychology,” Bulik says. “But my first class with John Cacioppo, who went on to create the field of social neuroscience, was a moment in my life when everything just clicked.”

Within a week of that class, Bulik was in Cacioppo’s office discussing projects that she could get involved in. Her path to psychology was set.

Several weeks later, her life course was altered again — this time at a football game.

“I was in the student section and these guys grabbed me from behind, lifted me up, and passed me over their heads to other people in the stands. I was scared to death,” Bulik says. “And then they dropped me. It broke my back.”

The injury impaired Bulik’s ability to move, and she went home to Pittsburgh to be with her parents for the rest of that semester. She continued her studies from afar, along with her relationship with Sullivan, whose care and support continued to strengthen their bond.

In the spring, Bulik returned to Notre Dame to pick up where she left off, all while learning to cope with the new limitations caused by her spine injury.

Travel and training

As the duo neared the end of their undergraduate studies, Sullivan was unsure of his next steps.

“I tried to write my personal statement for medical school and couldn’t get past the first sentence,” he says. “I took that as a sign that I needed to figure some things out, so I took time off and traveled across Europe.”

Meanwhile, Bulik went back to Pittsburgh to be a research associate in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. She dove into projects on sleep and depression and was introduced to the study of eating disorders.

“I shadowed the attending psychiatrist on the eating disorders unit,” Bulik says. “A lot of the patients were around my age and had severe anorexia nervosa, and it just hit me.”

Bulik was a figure skater and had been around eating disorders for most of her life but wasn’t able to identify them as such. No one had discussed that this was a health issue. It was an experience that defined the course of her career.

She made plans to pursue a clinical psychology graduate program at the University of California, Berkeley (UC-Berkeley). But before starting school, she joined Sullivan — who had been keeping in touch with postcards and the occasional (expensive) long distance phone call — on the tail end of his travels.

“Travel has always been important to us,” Bulik says. “In the beginning, I knew that even though we were very different people, our values have always aligned, and I think travel and adventure is one of those.”

And those travels gave Sullivan the direction he’d been searching for.

“I wrote my personal statement for medical school while standing up on a bus in northern Greece,” he says. “At that point, it was simple because I knew exactly what I wanted to do and why.”

And he knew where, too — California with Bulik.

Forging a joint path

In 1983, the dynamic duo started attending graduate programs at different universities in the San Francisco Bay Area. Bulik created her own course of studies in the emerging field of eating disorders at UC Berkeley, and Sullivan attended the UCSF School of Medicine, where his interest in psychiatry grew.

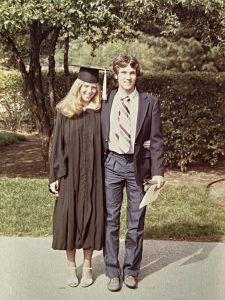

Then in 1986, in the middle of their graduate programs, they got married.

“It became blindingly obvious that we were deeply compatible, and marriage was the clear next step,” Sullivan says.

The couple finished their graduate programs in 1988, and launched careers that would take them across the country and world, all while growing a family.

Slideshow Caption: Their devotion to each other and science took them from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to Christchurch, New Zealand, to Richmond, Virginia, and finally, to Chapel Hill.

By 2003, Bulik and Sullivan had settled in Richmond, Virginia. So, when Bulik received a call from the UNC School of Medicine to apply for the first endowed professorship in eating disorders in the U.S., she turned it down.

“They were persistent,” Bulik says. “They had me visit campus at the end of March when the skies were blue and everything was in bloom, and the meetings with potential colleagues and collaborators were energizing.”

As it turned out, the newly formed Department of Genetics was looking for someone with Sullivan’s expertise, so the family moved one more time.

Making a research home

Bulik and Sullivan settled in quickly at Carolina and got to work creating care and research programs to support their ambitious goals.

In 2003, Bulik became the founding director of the Center of Excellence for Eating Disorders and has led it ever since. It’s a world-renowned center that focuses on clinical service, training, and research, which includes genetics-based collaborations with Sullivan’s lab.

“This program is near and dear to my heart,” Bulik says. “The genetics findings have established that anorexia nervosa is not only a psychiatric disorder but is also a metabolic disorder. We’ve opened this whole new line of inquiry to investigate the disease and ultimately to improve treatment.”

Sullivan worked to uncover why some people are more likely to suffer mental illness than others. In 2007, he co-founded the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, a group of more than 800 scientists from 36 countries. Collectively, the consortium has published around 600 papers and increased understanding of the basis of psychiatric disorders.

“Everything we learn, we make the information available publicly because we’re all about wanting to make things move as quickly as possible to understand the genomic and scientific implications of conditions like depression and schizophrenia,” Sullivan says.

During their time at UNC-Chapel Hill, Sullivan and Bulik also applied for separate grants to conduct research at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden. They were both awarded their grants — but found out at different times.

“My notification came before hers, which made for an awkward three weeks,” Sullivan says. “Yet, it is another example of the great fortune we’ve had over the years.”

From 2014-2020, the pair spent half their time in Sweden leading research teams. With their kids out of the nest, it was another adventure in science and life. And then the pandemic hit.

A legacy of collaboration

Bulik and Sullivan continued to lead their teams at Karolinska from afar, while redirecting some of their focus at home.

“I was able to get back into clinical practice with the Taking Care of Our Own Program, which provides psychiatric and psychological care for UNC medical professionals,” Sullivan says. “It was amazing to have the privilege of assisting these talented and dedicated individuals.”

On the heels of the pandemic in 2022, mental health was at the forefront of health care conversations. The Suicide Prevention Institute was established with Sullivan as its director. He pulled together a team of 40 faculty at the School of Medicine, including Bulik, to reduce suicide in patients seen across the UNC Health system and beyond.

“There’s an enormous amount of work to be done,” Bulik says. “We’re just getting started with the Suicide Prevention Institute, we still have teams in Sweden, and there’s still so much to learn about eating and other psychiatric disorders.”

Bulik and Sullivan are still working diligently to answer some of the biggest questions remaining in psychiatry and psychology. And now they also have a passion for training the next generation of researchers and clinicians to push forward the advancements they have made over decades together.

“I’ve had such great fortune to have met and consistently interact with Dr. Cindy Bulik for 45 years,” Sullivan says. “She’s an amazing human being.”

“We’ve grown up together as people because we met so young,” Bulik says. “And we’ve grown up together as scientists too.”

Cynthia Bulik is the Distinguished Professor of Eating Disorders within the UNC School of Medicine and founding director of the UNC Center of Excellence for Eating Disorders. She is also a professor of nutrition in the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health and associate director of the UNC Center for Psychiatric Genomics.

Patrick Sullivan is the Yeargan Distinguished Professor of Psychiatry and Genetics within the UNC School of Medicine and director of the Center for Psychiatric Genomics. He also leads the UNC Suicide Prevention Institute.