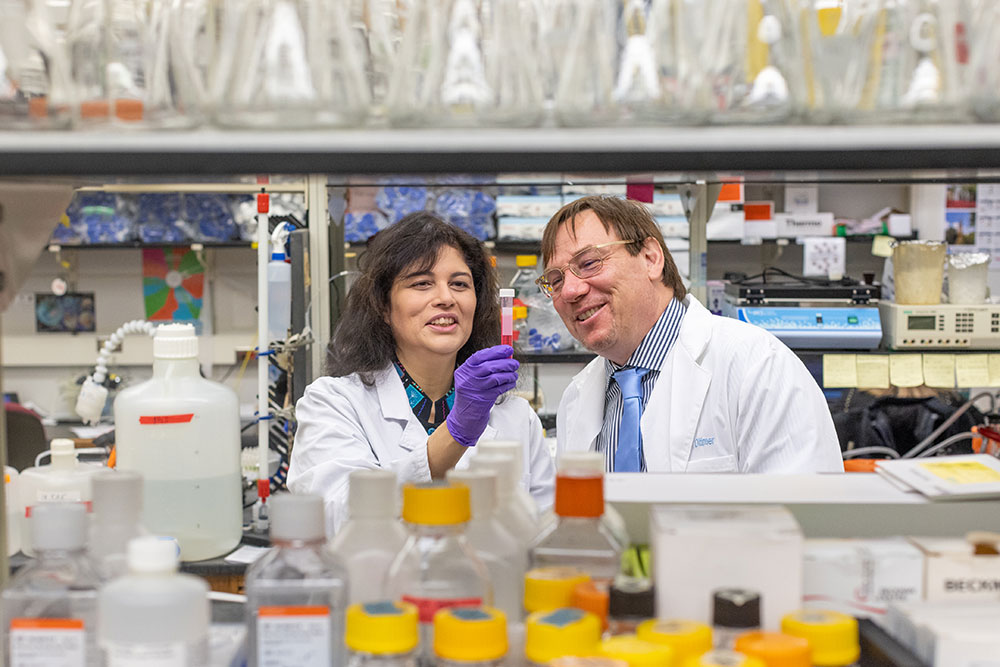

What started as a shared passion for science grew into love for virologists Blossom Damania and Dirk Dittmer, whose bond is continually strengthened through their commitment to research.

You could say science is the love language of Blossom Damania and Dirk Dittmer.

“Our lives are so intertwined with research that conversations at home about taking out the trash turn into discussions like, Oh, by the way, did you see that new paper that was published?” Dittmer says.

For over 20 years, the virologists have been collaborating in and out of the lab. Their relationship is timestamped with publications in peer-reviewed journals, 57 so far. They each have labs in the UNC School of Medicine’s Department of Microbiology and Immunology and the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center and collaborate frequently.

They differ in their research approach and staffing but share a common goal: to cure as many viral cancers as possible, but most specifically Kaposi’s sarcoma, a type of tumor caused by the Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), discovered by scientists about 30 years ago.

“There was really no way of avoiding running into Blossom,” Dittmer says fondly. “We were both working on tumor viruses, and there were only a few researchers in the field at that time. We later had some of the first papers on KSHV, and we needed to communicate about the science.”

In the ‘90s, Damania and Dittmer were earning their graduate degrees and pursuing postdoctoral fellowships — Damania at the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard, Dittmer at Princeton University and Stanford. They met at basic science conferences once a year for nearly a decade as colleagues, discussing their shared research interests, hoping to advance their work. But conferences offered more than a chance to talk shop.

“These conferences occasionally hosted excursions, and somehow Dirk was always in my group,” Damania says with a laugh.

“These conferences occasionally hosted excursions, and somehow Dirk was always in my group,” Damania says with a laugh.

Dittmer admits he used these opportunities to get to know Damania better.

“At one conference in Santa Cruz, California, they told us we needed to walk around campus in pairs because there were mountain lions around. I made sure I was paired up with Blossom,” Dittmer says.

And his efforts paid off. At the start of the new millennium, the two were still staying in touch.

“I had started my lab at Carolina, and Dirk, a year ahead of me, was still building his lab at the University of Oklahoma,” Damania says. “Starting our labs around the same time was a real bonding experience. Dirk would give me advice, we would collaborate on studies, and applied for grants together in 2001 and 2002. That’s when our relationship started to become more personal.”

In early 2002, Damania visited Dittmer in Oklahoma to finish a study they were working on that would result in their first publication together — and so began their years-long, long-distance relationship.

“Long-distance relationships are not atypical in academia,” Dittmer says. “We were married in 2003, but then we encountered what is called the ‘two-body problem,’ in which you need two open positions at an institution to recruit one of the researchers.”

Fortunately, Damania and Dittmer both worked at institutions that were forward-thinking at a time when couples weren’t often recruited as a package deal. The virologists were offered positions by both of their universities, but ultimately chose UNC-Chapel Hill as their home.

“In North Carolina, there were fewer tornadoes and more virologists,” Dittmer says.

In January 2004, Dittmer joined Damania at the School of Medicine and began building his own research lab. They employed different approaches to solving similar problems.

Damania describes herself as mechanistic. Over the past two decades, her lab has consistently studied cancers associated with oncogenic viruses — those that cause changes in the host cell’s genes that can result in tumors — primarily KSHV. Her lab strives to understand the specific mechanisms viruses use to induce cellular transformation, persist in the body, and evade the immune system.

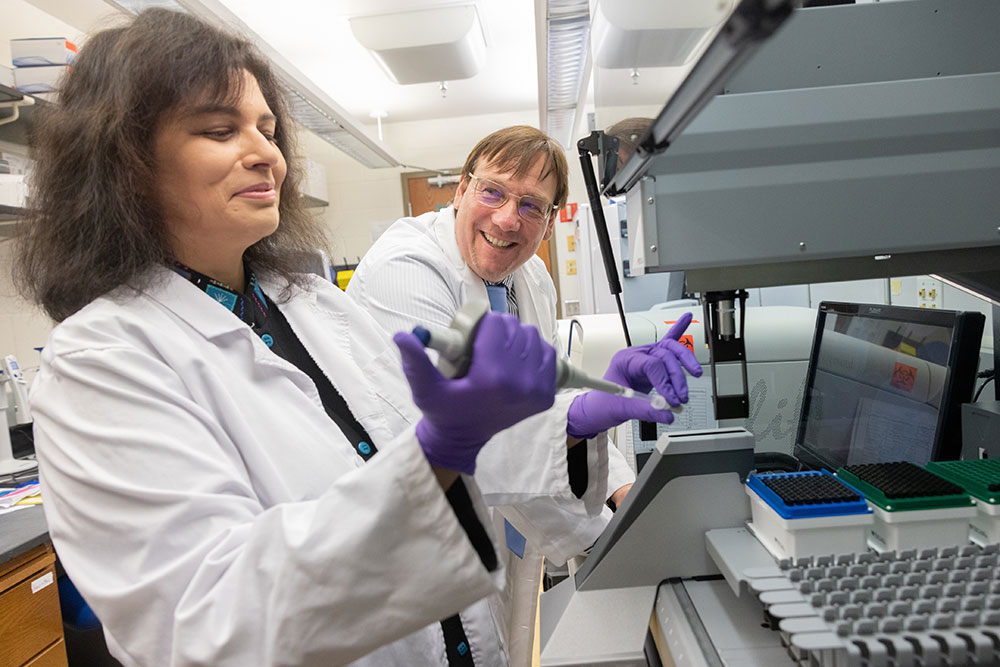

Dittmer is more of a technologist. His lab established the UNC Vironomics Core to study oncogenic viruses like KSHV with next-generation sequencing to examine viral genomes and viral gene expression in human specimens and tumor samples.

“We took our different views of science and applied it to joint research,” Damania says. “We always find ways to collaborate. As much as 25% of our work is done together.”

“We took our different views of science and applied it to joint research,” Damania says. “We always find ways to collaborate. As much as 25% of our work is done together.”

That collaboration has proven to be crucial for Carolina. In early 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic began in the U.S., Dittmer’s lab immediately started sequencing samples of SARS-CoV-2 to track the virus, and Damania’s lab members helped.

“We understood so little about COVID at that time,” Dittmer says. “The members of our labs knew each other from our weekly joint lab meetings, and that made them more comfortable working together in such a high-stress situation, allowing us to expand resources quickly and efficiently.”

Dittmer’s lab still tracks SARS-CoV-2 strains across the state with sequencing, even as their research has slowly returned to pre-pandemic topics. Both labs continue to make strides in KSHV research.

As Damania and Dittmer advance in their careers at UNC-Chapel Hill, they continue to present themselves to the Carolina community in a pragmatic way so that their relationship doesn’t dominate impressions of them as individual researchers. They do such a good job at keeping a low profile that quite a few students and staff in the school aren’t aware of their marital ties.

“I teach introduction to virology and at the end of the class the students are always asked to give feedback by answering, What was one of the most interesting things you learned?” Dittmer says. “One student’s answer was that Blossom and I are married.”

The research duo serves as an example to other couples that relationships in academia are not only possible but can thrive. They are routinely called upon for advice and are happy to provide it.

“The two-body problem is still present,” Damania says. “So when graduate students ask us how to navigate a certain challenge, or other scientists seek us out at conferences with personal questions, we listen and offer guidance.”

And yes, the two are still going to conferences together, even towing along their offspring over the years. Because after all, science is what drew them together in the first place.

Blossom Damania is the Boshamer Distinguished Professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology, a professor in the Department of Pharmacology, and vice dean for research within the UNC School of Medicine. She is also co-director of the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center’s Virology and Global Oncology programs.

Dirk Dittmer is a professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology and director of the UNC Vironomics Core within the UNC School of Medicine. He is also co-director of the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center’s Virology and Global Oncology programs.