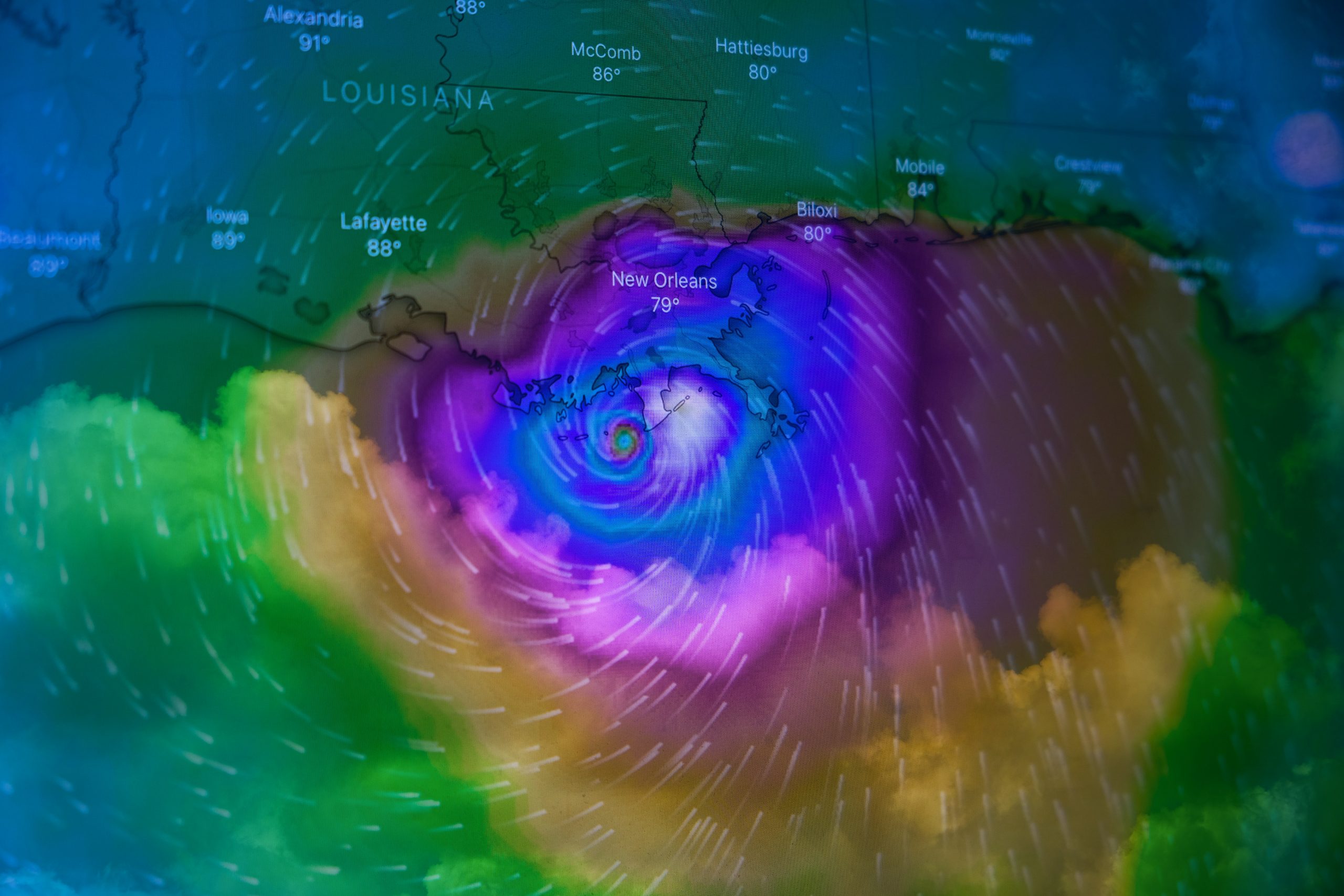

On Sunday August 29th, Hurricane Ida made landfall in New Orleans as a Category 4 hurricane, but thanks to the work of UNC researcher Rick Luettich and others, the levees held and water damage was greatly minimized.

ADCIRC is a computer program co-developed by Luettich and researchers from the UNC Institute of Marine Sciences, Coastal Resilience Center for Excellence, and the Renaissance Computing Institute. It helps determine what coastal oceans will do when a big storm comes. Luettich said these predictions can inform us of what hazards coastal areas will face going forward and how we can better prepare for them.

Sixteen years ago, New Orleans was devastated when Hurricane Katrina resulted in the deaths of 1,833 people. The majority of those deaths were attributed to flooding that resulted from the failure of the city’s levee system. While hurricanes are rated from Category 1 to Category 5 on a scale of wind speed, Luettich said storm surge and flooding is where most of the damage comes from.

“Right after Katrina, a massive forensic study led by the Army Corps of Engineers was conducted to recreate the conditions under which the levees failed,” Luettich said. “We helped the study team use ADCIRC to go back and determine the storm surge conditions that led to the failures and how high the levees needed to be to protect the city from future storms.”

Luettich’s contributions did not end after he made recommendations for the new levees. In 2012 he was appointed by the Governor of Louisiana as a Commissioner on the Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority which oversees the protection system lying east of the Mississippi River. He served on this board until 2019, helping to lead the reorganization of the Authority to improve efficiency and minimize the potential for failures across the system.

“The greater New Orleans area is comprised of three parishes,” Luettich said. “At the time of Katrina, each parish operated its own levy district. The problem with that is they weren’t all self-contained units from a flooding standpoint, so if one parish didn’t live up to its responsibility there was a weak link in the chain and water could overtop the levees.”

Luettich’s expertise in storm surge and flooding meant he brought a strong, scientific perspective and motivation to guide the consolidation of the levee systems into a single cohesive organizational system.

As Ida was approaching New Orleans, Luettich’s ADCIRC program was busy running predictions to determine whether the storm surge would overtop the new levees. As his models predicted, the storm did not bring the same intensity in flooding as Katrina, but it did serve as an important test.

“Before the levees can pass a Katrina test they needed to pass an Ida test,” Luettich said. “And an Ida test wasn’t small potatoes, but the new system, both the infrastructure and the organization required to maintain and operate it, seemed to pass in flying colors.”

The work Luettich does in New Orleans allows him to bring new knowledge and expertise back to North Carolina, where he conducts most of his research with the Institute of Marine Sciences.

“There’s a whole lot of people that want to live in coastal areas and many of them are subject to the ever-increasing threat of flooding due to our changing climate,” Luettich said. “Until people decide that they’re not going to live in these hazardous areas anymore, somebody needs to be thinking about how to quantify and understand the hazard so we can live with them as effectively as possible. That’s a lot of what coastal resilience really is.”

Rick Luettich is director of the UNC Institute of Marine Sciences and lead principal investigator of the Coastal Resilience Center of Excellence. He is an Alumni Distinguished Professor with academic appointments in the Department of Earth, Marine and Environmental Sciences within the UNC College of Arts & Sciences and in the Department of Environmental Sciences and Engineering within the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health.