A dying septic system and lack of public sewer are slowly putting Woods Diner and Store out of business. Woods has been serving up sandwiches, burgers, and live bluegrass music in Polkville, North Carolina (population 535), for the past forty years. But the diner couldn’t afford to repair its septic tank. The lumber company across the street had the same kind of problem — it had been relying on a portable toilet for twenty-five years.

“Even though there was a trunk line for sewer less than a quarter-mile from both of these businesses’ doorsteps, it would take a couple hundred thousand dollars to hook them up to it,” Alison Gillette says. “Cleveland County has the second-highest number of incorporated municipalities in the state, many of which are too small to fund their own water and sewer systems.” So Gillette went to work helping the town find and apply for the funding it needed to help the businesses.

Gillette is one of nine members of the Carolina Economic Recovery Corps, a group of Carolina graduate students and fresh-out-of-grad-school professionals who fanned out across the state in the summer of 2009 to help communities research and apply for federal stimulus funding.

When the federal government announced the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, says Jesse White, director of the Office of Economic and Business Development (OEBD), his office and other people from around campus got together to find out what the act could mean for North Carolina’s small towns. And what they found, after talking with officials from around the state, was that most wouldn’t have a chance of getting funding without what White calls “boots on the ground.”

“What we heard was, ‘Send somebody to help us,’” he says.

Applying for Recovery Act funding — even just understanding the regulations — requires hundreds of staff hours, White says. And many of the most impoverished towns in North Carolina also have the least infrastructure. “Some of them don’t have town managers, some of them don’t have staffs,” he says. “Some of them may have a part-time clerk.” So even if they were able to win a federal grant, they’d have a hard time complying with all the regulations and monitoring their progress.

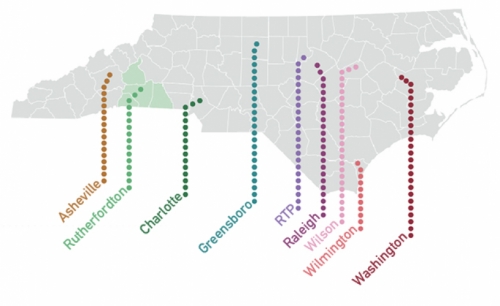

Graphic by Jason Smith. ©2010 Endeavors magazine.

This map shows the locations of the CERC projects. The Isothermal Planning and Development Commission is part of a four-county region (shown in green) containing 28 municipalities ranging in population from 184 to nearly 21,000. Seventeen of the municipalities have fewer than 1,000 people, and eight municipalities have fewer than 500. All of these smaller municipalities are served by a part-time mayor and part-time clerk, who are employed by the Town of Rutherfordton.

Click to read photo caption. Graphic by Jason Smith. ©2010 Endeavors magazine.

Within weeks, the Carolina Economic Recovery Corps was fully formed, and OEBD had dispatched interns to eight different councils of government around the state — many to North Carolina’s most distressed areas.

Gillette was stationed with the Isothermal Planning and Development Commission, the council of government in nearby Rutherfordton, a quiet town of about four thousand people. (Councils of government are associations of county and municipal governments that provide planning and other services for their regions.) She spent the summer researching and applying for grants, knocking on doors to collect survey information, and making friends with the locals. One of her projects was to help Woods Diner and Store get funding to connect to public sewer so the owners could stay in business, expand, and create more jobs.

Image by Jason Smith. ©2010 Endeavors magazine.

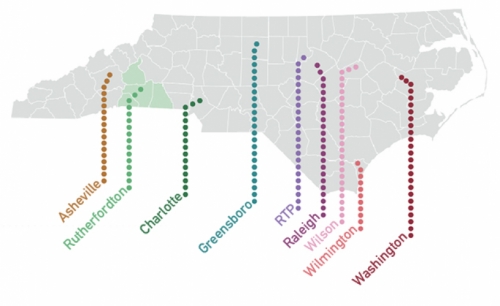

The situation on the ground: Almost all N.C. municipalities that have a population greater than 5,000 are applying for some type of stimulus funding. Smaller towns are less likely to apply, but at least 140 municipalities that have a population below 5,000 are applying. Many of these towns lack the staff capacity and experience to apply for these grants or meet their compliance requirements.

Click to read photo caption. Image by Jason Smith. ©2010 Endeavors magazine.

Brian Taylor, a student in the Department of City and Regional Planning, interned at the N.C. League of Municipalities in Raleigh. He created an inventory of all 550 municipalities and 100 counties in the state to show which ones are applying (or have applied) for federal funding. No one in any state had ever built a system to track applicants, although most state governments track grant recipients. In the future, it’ll serve as a measure of how effective the stimulus act has been in reaching small towns such as Polkville. But the inventory will also help the state provide better support for those who’ve applied for funding, including help with technical matters, compliance, and reporting — all of which are part of Gillette’s new job in the N.C. Office of Economic Recovery and Investment.

In fact, she and three other Carolina Economic Recovery Corps interns who’d already graduated from their programs at UNC were hired for full-time positions, either by the state or with the councils of government they had worked with over the summer. Several others are continuing their work part-time now that their classes at UNC are back in session. And OEBD plans to continue the program for at least the next two years.

Gillette’s still waiting to find out whether the Polkville businesses will get the funding they need. But she’s excited to keep working with the towns around Rutherfordton. The chance to work with local communities is exactly why she wanted to study city and regional planning in the first place, she says. “I was hoping to put all of my studies to work in a practical setting. And it’s been fascinating. I really like it out here.”