After arguing with his ex-girlfriend, Michael was so distraught that he got in his car and headed to the liquor store. As he drove, he remembered what his therapist had said: it was exactly this reaction to stress that had led to ruined relationships and nights in jail.

Michael took a deep breath, turned the car around, and went home. Did Michael muster some sort of mysterious willpower? Maybe. But behavioral neuroscientist Charlotte Boettiger says Michael may have trained his brain to think longer and harder about long-term consequences — something alcoholics struggle to do, she says.

“We know how valuable this sort of cognitive behavioral therapy is,” Boettiger says. “But we don’t understand how the brain tends us to make short-sighted decisions or decisions that are good for the long term.”

She designed a study to try to find out. She asked sober alcoholics (people who are addicted but no longer drink) and people with no history of alcohol abuse to choose between immediate rewards and larger rewards that would come later on. For instance, in one trial participants had to decide between taking seventy-five dollars right away or one hundred dollars in two weeks. Boettiger controlled for factors such as economic status and I.Q.

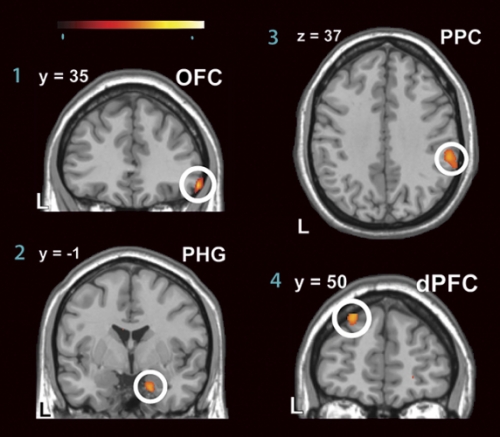

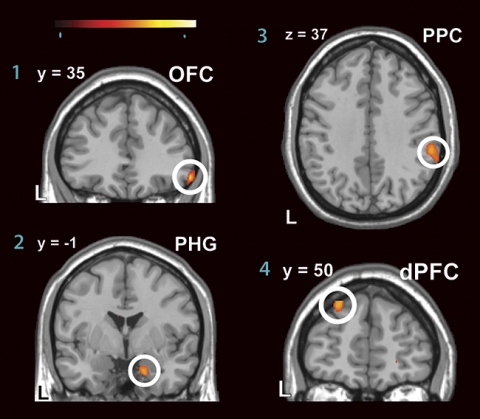

While the participants were making decisions, Boettiger used functional magnetic resonance imaging to measure activity in different parts of their brains. She found that sober alcoholics chose the immediate reward much more often than did people with no history of alcohol abuse, and that four parts of the brain in sober alcoholics apparently react to decision-making differently. For instance, the orbitofrontal cortex, which is directly above the eyes, was less active in sober alcoholics.

“This was most exciting for me because of all the areas in the brain, it’s the one most commonly associated with addiction and related disorders such as obsessive compulsive disorder,” Boettiger says. “And clinicians have already linked damage to the orbitofrontal cortex to personal management problems — handling money and relationships, and acting on long-term consequences.”

She says the orbitofrontal cortex may be involved in contemplating abstract consequences to make them more concrete. So sober alcoholics who showed less orbito-frontal cortex activity in Boettiger’s test may have had trouble forming mental representations of important but abstract long-term consequences — for example, the abstract benefit that may come from having an extra twenty-five dollars in two weeks.

Boettiger says that this may be one reason why cognitive interventions can work; the therapy helps addicts visualize what will happen after they take that first drink. In Michael’s case, he could turn his car around because the long-term consequences weren’t so abstract — and driving to the liquor store didn’t seem like a good idea anymore.

Charlotte Boettiger is an assistant professor of psychology in the College of Arts and Sciences. She received funding from the U.S. Department of Defense to study cognition and alcohol addiction.