Threefold Sun. By Taj Forer. Charta Art Books, 135 pages, $59.95.

It was two thirty in the morning and photographer Taj Forer’s pickup truck was bumping along the back roads of western Tennessee. He’d gotten a late start, and he was sure that his host, a local farmer, would have gone to sleep hours ago. The road changed from asphalt to gravel to dirt before it finally ended at a little house, where a warm, friendly glow shone through the windows.

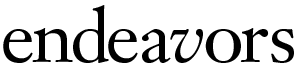

The music coming from inside stopped when Forer knocked on the door. Jeff Poppen, known to his friends and neighbors as The Barefoot Farmer, answered. “You must be Taj,” he said. “Welcome! Come on in.” Inside, several of Poppen’s friends sat around a blazing woodstove, each holding a musical instrument. They’d been picking out bluegrass tunes all night long.

Poppen’s Long Hungry Creek Farm was the first stop on Forer’s trek across the United States; he was looking for images of schools, people, landscapes, and other subjects that in some way embodied the things he’d learned at his childhood Waldorf school in rural New Jersey. For over a month, with only his camera to keep him company, Forer rambled along in his biodiesel pickup, stopping occasionally to refuel from grease traps at fast-food restaurants.

There are only about a hundred Waldorf schools in the United States, and their curricula are based on the teachings of early-twentieth-century philosopher and agriculturalist Rudolf Steiner, who wanted young students to have the freedom and experience to be “childlike enough.” So teachers in Waldorf schools take a holistic approach to education, and often combine tactile lessons with academic ones. For example, along with reading and math, kids might learn how to tend a garden, grind wheat for bread, or build a waterproof shelter in the woods.

Steiner also developed an agricultural method known as biodynamic farming. Everything that’s produced on a biodynamic farm is also somehow consumed, so the farm becomes a sort of self-nourishing organism. Steiner wanted not only to heal farm soil that had been sucked dry of its nutrients, but also to connect the ecology of the living farm to the workings of the entire cosmos. Imagine preparing your fertilizer by plugging a hollow cow-horn with a mishmash of manure, soil, and other farm miscellany, and then burying the concoction until the stars align just right.

“These things can sound a little hokey,” Forer says. “But they work.”

Forer made camp at Long Hungry Creek Farm because Poppen has worked his land biodynamically for the past twenty years. And he’s been incredibly successful. Aside from his vast vegetable crops, fifteen-year-old strawberry patch, and small herd of cattle, Poppen has over a hundred subscribers to his produce through community-supported agriculture.

“He doesn’t eat anything he doesn’t produce,” Forer says, “and his skin just glows.”

The morning after Forer arrived at Poppen’s place, they toured around the three-hundred-acre farm, which Poppen manages with the help of one farmhand. They worked together for hours in the January cold, Poppen without shoes the entire time. After that Forer set up his Hasselblad camera.

One of Forer’s photographs from Long Hungry Creek Farm shows Poppen with one bare foot propped comfortably on a stack of cedar logs, looking for all the world as if he’s just sprouted from the cold ground himself. Another is of Poppen’s stepson: he sits loosely on a tree stump in jeans too big for him; even though it’s January, his arms and feet are bare, and he looks quizzically at the camera.

The child in that photo is just a little younger than Forer was when, after finding an old camera in his parents’ basement, he became obsessed with color photography. “One of the great struggles for me as a photographer, though, is the fact that I do work with color,” he says. The chemicals necessary for making film, developing it, and creating prints all eventually wind up in the water table, he says, and that really weighs on him. “At the same time, I think there’s something to be said for using the medium to explore issues and raise questions in people’s minds about our relationship with the natural environment.”

After a few days at Poppen’s farm, Forer moved on to Waldorf schools and bio-dynamic farms across the country. Most of the resulting photographs in his new book, Threefold Sun, were made during the winter, and many of the plates depict wintry landscapes. A hill beneath a swing set where the snow has been worn away by too many sleds. Two young girls bundled up and nestled in a fort made of hay. A single corn husk angel lifted on a reedy stalk against a flat, stony sky.

But it’s in many of the portraits and interiors — warm kitchens, Valentine-strewn cafeterias, a schoolboy with a bloody nose — that the color in Forer’s photographs is indispensable.

“My dream is to live on a small farm and grow most of my own food,” Forer says. “Live a little more simplistically and emphasize agriculture as part of my daily life.” So he does the best he can to find a balance for his two passions — a simple pastoral existence on the one hand and a highly technical, mechanized art form on the other.

In one of Forer’s photographs from a Waldorf school in Tucson, Arizona, two chalkboards hang side by side on a painted cinder block wall. In neat yellow cursive, one reads:

We will buy 2 trios of rabbits

$60.00 each = $120.00

Each child will earn and bring

$6.10.

And beside it:

Everyone does the

best they can.

Taj Forer is a graduate student in the Master of Fine Arts program at Carolina. He received funding for his work in Threefold Sun from the Rudolf Steiner Foundation. He is an Artist-in-Residence at the North Carolina Contemporary Art Museum and editor of the photography journal Daylight Magazine.