We think we know their stories. They are Mexican immigrants here to earn money to support families back home. Carolina anthropologist Hannah Gill understands this, but she’s more interested in the details behind the dollar signs. So after earning a doctorate from Oxford in anthropology and Latin American migration, she returned to her native North Carolina to research the state’s burgeoning immigrant population. She found a new way to listen to immigrants’ issues, and learned that what happens back home is just as important as what happens here.

Her first stop was El Centro Latino, an advocacy and service center in Carrboro. Gill stands out as a volunteer, but she speaks fluent Spanish and wants to help. Her goal was to gain trust and then tell migrants about her oral history project — a book to be published in their own voices. She met dozens of people before spotting a trend.

“Celaya, Celaya, everyone was from Celaya,” she says. About 75 percent of North Carolina’s 600,000 Hispanics are Mexican. And in Orange County, most Mexicans are from Celaya, a decaying manufacturing center of 383,000 people, situated 125 miles northwest of Mexico City. Downtown is surrounded by poor villages, sweatshops, and, further out, agricultural fields. When Celayenses want to get a leg up, they look to the United States.

Angela, one of Gill’s thirty-two oral history participants, says that money earned in the States goes back to Celaya for schooling, lunches, uniforms, and transportation to school. “Before, the majority of children couldn’t study past elementary school because you have to pay for high school,” Angela says. “Now they can.”

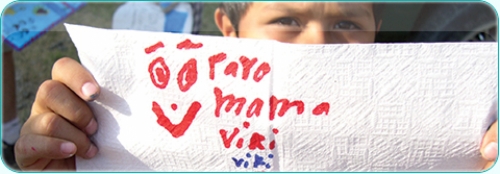

Hannah Gill traveled to Mexico to see how emigration affects the people left behind. Photo: Jason Smith.

Art as an opener

But there’s more to the story back in Mexico.

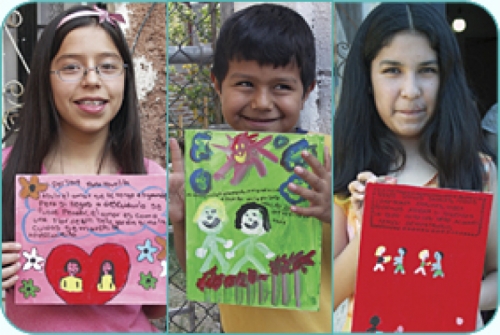

Gill traveled to Celaya with artist Todd Drake, an exuberant painter who prefers community building over the solitary artist’s life. He asks students to paint personal themes. Then he incorporates their art into a much larger painting of his own. In Celaya, he helped families create paintings in the Mexican tradition of ex-votos, which typically are small religious paintings placed on church altars to commemorate miraculous events. As Drake guided workshops, Gill recorded conversations. Themes of loneliness, money, sentimentality, and religion came through. The biggest issue, though, was separation of families.

“One of the villages we visited was devoid of men,” Gill says. “It was surreal. What was surprising was that most women said they would prefer that their husbands and sons come home and live in poverty.” Several told Gill that Mexico is home; the United States is for money.

“You can see how families in Mexico benefit monetarily,” Gill says. “They can put a roof on their house but, when you talk to them, they are sad because all the men are gone.”

One woman from a village west of Celaya told Gill, “One hundred percent of us have families in the United States.”

Gill spoke to Celayenses educators who said schools now try to fill roles traditionally held by men. Teachers spoke about moral education and teaching life skills. Gill says some Celayenses attribute increases in drug abuse and drop-out rates to migration.

A teacher in Celaya told Gill, “The kids miss their dads, and can’t concentrate in school as well. You see a huge change in winter, when a lot of the men come back. The students are animated and excited to learn. Unfortunately, some parents never return and families disintegrate. This tends to happen more.”

With the help of Todd Drake, these children from Celaya created paintings about emigration. Photos: Todd Drake

Loyalty means everything

Some men are extremely faithful and send money home regularly. Others aren’t and don’t.

Saul, a Celaya resident, told Gill, “There are people who, after three months, forget their family. They meet another señorita, maybe more pretty or young, or maybe they have left their wife. There are a lot of people like this.”

Another told Gill, “Some men change a lot. There are many who don’t come back, many who never call. They don’t communicate. They leave their families here, their wives. They find new families and stay.”

In 1994, sixty-four Mexicans lived in Carrboro. Now there are about two thousand. Most come directly from Celaya. Over the past ten years, though, some migrants came from California, which has been home to a large Hispanic population ever since the United States annexed part of Mexico in 1848. Gill says that some settled Mexicans in California are hostile to newcomers.

“Settled Mexicans get lumped into the category of Mexicans using up tax dollars and all the stereotypes,” Gill says. “They want to be distinct from new immigrants.”

Josefina, another oral history participant, told Gill, “In North Carolina, Hispaños treat each other better because everyone is new. No one thinks he is better than anyone else. In California, new immigrants are treated terribly by second generations.” She told Gill that she didn’t want her grandson to grow up in that atmosphere. A mother of five whose husband died several years ago, Josefina couldn’t find a job that paid enough in Mexico. She heard there were jobs in North Carolina, so they moved to Carrboro, where she lives with her daughter and son-in-law.

“Of course, the flip side is that the Americanos treat you worse in North Carolina,” she said. “We are not terrorists! We are people just like anyone else, trying our best to help our families back home.”

Need versus danger

In the 1990’s, the Mexican economy tumbled as ours boomed. Mexicans flocked north to fill jobs in construction, meat processing, and farming, all at the lower end of the pay scale. Many migrants new to California came east when word of mouth reached them about the South’s affordable living and growing economy.

By 2000, Latinos made up 50 percent of North Carolina’s meat processing work force, and 75 percent of Charlotte’s construction jobs. More than 25 percent of all Triangle carpenters, construction laborers, painters, and food processors were Latino. Migrant labor is in demand throughout the state, including Smithfield Foods down east, Case Farms in Morganton, Tyson Farms Chicken in Siler City, and the High Point furniture manufacturers. A recent Kenan-Flagler Business School study showed that Hispanics contribute more than nine billion dollars annually to the state economy. The amount could total eighteen billion by 2009. Immigration’s drain on health care, education, and correctional services doesn’t come close to equaling either figure, the report says.

But before Hispanics reach North Carolina, they often take an arduous journey, as Gill’s students found out. Last fall, Sarah Plastino, a junior public policy and international studies major, took Gill’s course, “Immigrant Perspectives,” which Plastino says taught her more than any other class at Carolina. As a part of her research on pregnancy, birth, and motherhood in the migrant community, Plastino met a woman at El Centro Latino who had been five months pregnant when she walked across the border into Texas.

“She told me how helpless she felt due to the language barrier during prenatal care,” Plastino says. “She spent the rest of her pregnancy alone and isolated. Her husband worked long hours while she was unable to drive.” The woman told Plastino that she could only assume her baby was healthy when nurses said she could leave.

Gill also heard harrowing stories. Since Celaya sees a lot of emigration, the town has a lot of “coyotes” — people paid to drive truckloads of Mexicans across the border. The price for coyote transport has increased substantially due to tougher American border patrols.

“It’s now more lucrative to smuggle humans than drugs,” Gill says. “So these dangerous criminals now dabble in smuggling people. Some people kidnap migrants from coyotes and hold them for ransom. If they don’t get paid — well, there have been reports of migrants being killed.”

Typically, migrants pay part of the money before the trip and the rest at the coyote house across the border. Sometimes families of migrants, either in Mexico or in the States, are supposed to pay or meet the coyotes once across the border. Gill says that when neither shows up in time, some migrant women prostitute themselves to get out. Others have reported rape. Some women now refuse to travel alone and many others refuse to leave Mexico.

Gill’s work adds a different voice to the immigration debate. She believes that many Mexicans would rather stay home. With this in mind, she will head back to Mexico this summer to document more stories, as well as needs, such as potable water and working toilets in Celaya’s village schools. Her goal is to link Mexican Rotary clubs with American Rotarians. She will also present her findings to North Carolina Rotary clubs to raise awareness and, she hopes, money for projects back in Mexico.

“There’s a way to get at the root of immigration,” Gill says. “It’s not about fortifying the border. Improving conditions in Mexico can help.”

Hannah Gill and Todd Drake were 2004-05 Rockefeller Fellows at the University Center for International Studies (UCIS), which hired Gill in 2005 as a research associate to head its Celaya Project. Its aim is to link universities here with those near Celaya. UCIS Executive Director Niklaus Steiner and Research Associate Beatriz-Riefkohl-Muñiz (now Associate Director of the Institute for Latin American Studies) were part of Gill’s research team in Celaya. Sarah Plastino will go to Mexico this summer to research the impact of emigration on new mothers. She will also travel into Celaya’s villages with a mobile medical unit dedicated to helping the underprivileged. Gill’s book, Going to Carolina del Norte: Narrating Mexican Migrant Experiences, was published this spring.